Health Reform Could Outlast Repeal Efforts

Deep Changes Made in How Care Is Given

FISHERS, Ind. — Fragments of bone and cartilage arced across the operating room as Dr. R. Michael Meneghini drilled into the knee of his first patient at a hospital here at dawn. Within an hour, the 66-year-old woman had a replacement joint made of titanium and cobalt chrome, and she was sent home the next day.

But the Obama administration was watching over her caregivers’ shoulders. If, over three months, her medical costs exceeded a target amount set by President Obama’s health regulators in Washington, Dr. Meneghini’s employer, Indiana University Health, stood to lose money.

Such efforts to squeeze spending out of the nation’s health system may well remain as Mr. Obama exits the West Wing and Donald J. Trump takes his seat in the Oval Office. The Affordable Care Act is in extreme peril, and Mr. Obama will meet with congressional Democrats at the Capitol on Wednesday to try to devise a strategy that can stave off the quick-strike repeal of the health law that Republicans plan for the opening months of the Trump administration.

But the transformation of American health care that has occurred over the last eight years — touching every aspect of the system, down to a knee replacement in the nation’s heartland — has a momentum that could prove impossible to stop.

Expanding insurance coverage to more than 20 million Americans is among Mr. Obama’s proudest accomplishments, but the changes he has pushed go deeper. They have had an impact on every level of care — from what happens during checkups and surgery to how doctors and hospitals are paid, how their results are measured and how they work together.

“From the moment I first set foot in the Oval Office in February 2009, the president told me that the law can’t be just about covering the uninsured, but that it also has to be about changing the way care is delivered,” said Nancy-Ann De- Parle, who as a White House aide helped lead the effort to pass and carry out the health law. His message, she said: “I don’t want to cover everyone and just put them in the same creaky old delivery system.”

Changes in the delivery system already affect far more people than the law’s higher-profile coverage gains. To visit IU Health, the largest health care provider in Indiana, with 15 hospitals and 8,700 doctors, is to see those changes up close. Its leaders have started moving away from fee-for-service medicine, where every procedure, examination and prescription fetches a price. The emphasis now is on preventive care, on taking responsibility for the health of patients not only in the hospital, but also in the community.

Social work has become a larger part of the medical mission. Collaboration between doctors is becoming a necessity.

“I don’t know who could be against it: higher quality and lower cost,” said Ryan C. Kitchell, an executive vice president and the chief administrative officer of IU Health.

And unlike Mr. Obama’s insurance coverage expansions, these changes are not in jeopardy, said Dennis M. Murphy, IU Health’s president and chief executive.

“We’ve got to create more value in health care,” Mr. Murphy said in an interview after Mr. Trump’s election. “That principle, I think, survives.”

During Mr. Obama’s tenure, big systems like IU Health have gobbled up smaller hospitals and physician groups as the industry has consolidated, partly in response to incentives in the Affordable Care Act. Most doctors across the United States are using electronic medical records, installed in many cases with federal money provided by the economic stimulus law of 2009. The federal government and private insurers are rewarding health care providers that work together to coordinate care and avoid unnecessary expenses.

Doctors and hospitals here are obsessed with metrics, not least because under the health law, they may be rewarded or penalized based on their performance. They tally the number of medication errors, the number of patients injured in falls and the number who develop infections after certain types of surgery.

Expanding coverage is seen not as a political issue, but as a clinical and financial imperative. IU Health has more than 150 “navigators” who work with patients to help them get insurance, often through a Medicaid expansion authorized and funded by the health law and engineered here by Gov. Mike Pence, the vice president-elect.

“I’ve been a registered Republican my whole life, but I support the Affordable Care Act,” said Dr. Gregory C. Kiray, cochief of primary care for IU Health Physicians, “because it allows patients to be taken care of.”

To better understand how Mr. Obama has changed health care, two reporters from The New York Times spent a week shadowing and talking to doctors, patients, executives and others at IU Health, a system that demonstrates the breadth of changes catalyzed by the Affordable Care Act.

To many IU Health employees, the pace of change can be bewildering, the new directives too numerous or burdensome.

“People feel like they are swimming in an ocean, drowning,” said Dr. Meneghini, an orthopedic surgeon at IU Health’s Saxony Hospital here in Fishers, a suburb of Indianapolis.

But the medical profession increasingly understands that painful as it is, the revolution is necessary and unstoppable.

“The national economy cannot sustain health care being as big a share of the gross domestic product as it is,” Mr. Murphy said, uttering what once amounted to heresy for a health care provider.

‘Be Thoughtfully Aggressive’

Fury over the Affordable Care Act helped jump-start the Tea Party movement and sweep Republicans into control of the House of Representatives in 2010 and the Senate in 2014. It ensured gridlock that stifled many of Mr. Obama’s greatest legislative ambitions for six of his eight years in office, and it may well have played a role in the election of Mr. Trump, who attacked the law throughout his campaign.

Yet to Mr. Obama, the law remains one of his greatest achievements, said Denis McDonough, the White House chief of staff. It also has been his constant concern.

“This attention to cost and concern about cost, and even the emotional concern about cost, comes up all the time,” Mr. McDonough said.

The Affordable Care Act gave the government sweeping authority to test new models of care, and the administration has aggressively used that power to try different ways of paying for cancer care, heart surgery, primary care and other services covered by Medicare and Medicaid.

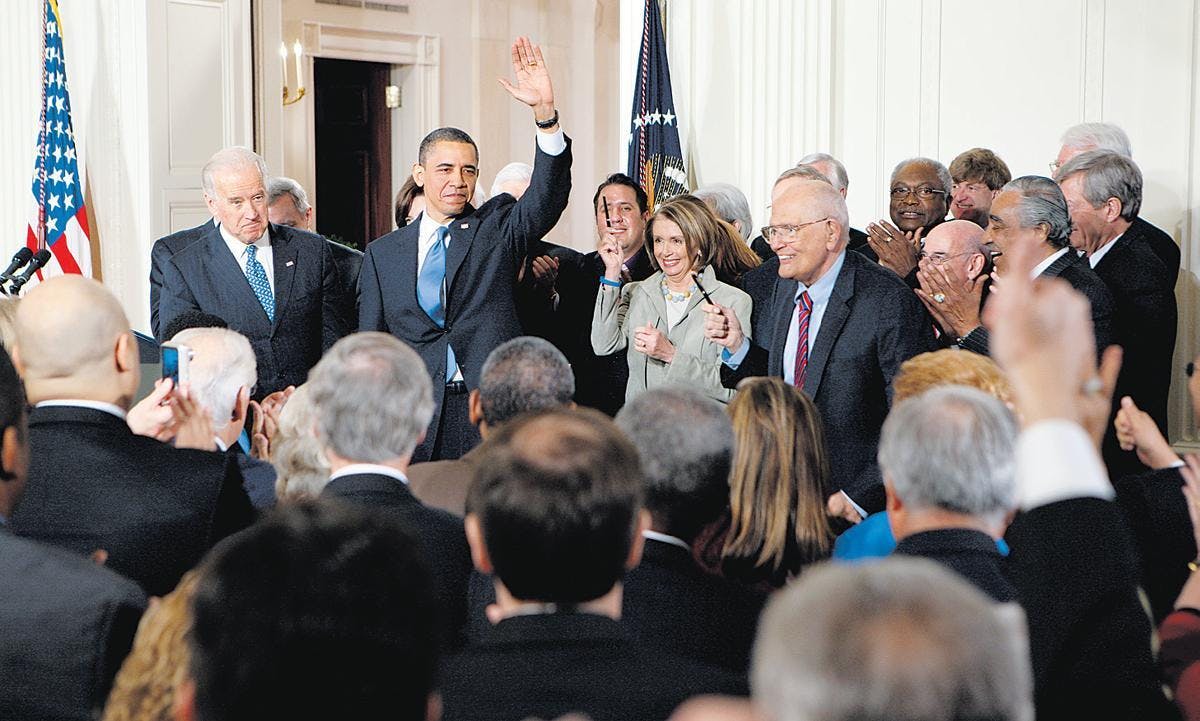

THE OBAMA ERA

Sylvia Mathews Burwell, who has been the secretary of health and human services since 2014, said she met with Mr. Obama early in her tenure to describe a series of payment and delivery reforms. He was so supportive, she said, that she and her team decided to undertake even more changes.

The size and speed of some of those initiatives have provoked criticism from Republicans, including Representative Tom Price of Georgia, picked by Mr. Trump to be the health and human services secretary. They say the efforts threaten the quality of care and exceed the authority of the agency overseeing Medicare by requiring doctors and hospitals to participate.

More than 170 House Republicans signed a recent letter of which Mr. Price was an author, urging the administration to “stop experimenting with Americans’ health.”

But moving aggressively to change how medical care is delivered and paid for has been important to Mr. Obama. In 2015, his administration set a goal for half of all Medicare payments to be tied to the quality, instead of the quantity, of care that doctors and hospitals provide by 2018. Mr. Obama believes that basing pay on whether a doctor visit or a medical procedure helps a patient, rather than on how much care the patient receives, will result in better care.

“What he said was, ‘Be thoughtfully aggressive,’” Ms. Burwell said.

At Patients’ Service and Mercy

“I started drinking soda again,” confessed Willie Johnson, a 52-year-old patient with uncontrolled diabetes and high blood pressure.

“How much?” Dr. Michael E. Busha, a primary care physician at IU Health in Indianapolis, asked quietly as he updated Mr. Johnson’s electronic record.

“Quite a bit.”

For Dr. Busha, that mattered.

He helps lead the IU system’s effort to measure how well doctors do at keeping patients healthy. And even this champion of “quality measures” — vital to the Obama administration’s goal of paying doctors based on outcomes, not the amount of care — has found that it is not always easy to meet them.

If enough of his patients fall below the standards set by IU Health, Dr. Busha could lose some of his income. The average salary for the system’s primary care doctors is $236,000. Of that, $50,000 is tied to meeting benchmarks for quality, access (whether a doctor agrees to see patients on weekends and at night, for example) and other performance measures.

Mr. Johnson, who registers patients when they arrive for neurology appointments at IU Health Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis, was not helping. He also had stopped taking his cholesterol medicine because it left a bad taste in his mouth. And he was using neither the gym membership that IU Health helps pay for nor his sleep apnea machine. “I never could get adjusted to it,” he told the doctor. Like other primary care doctors at IU Health, Dr. Busha is part of a team that includes a pharmacist, a social worker and a “care manager.” Such teams, encouraged by the health law, focus on patients like Mr. Johnson who are not meeting IU Health’s quality measures, and who are disproportionately likely to end up in the emergency room or be hospitalized.

“The whole paradigm now is to identify your high-risk people and provide more resources to them, provide better care to them, keep them out of the hospital,” said Dr. Kiray, the primary care cochief.

Partly because of these efforts, IU Health’s two adult hospitals in downtown Indianapolis are already seeing 12 percent fewer inpatients than they were in 2013. The system is merging the two hospitals into a $1 billion medical center focused heavily on outpatient care.

President Obama would be proud. Administration officials have continually emphasized the importance of primary care and the “social determinants” of health. They have offered grants to health care providers to identify Medicaid and Medicare patients with unmet social needs: inadequate food supplies, unpaid rent or utility bills and experience with violence at home, for example.

But with some patients, only so much can be done: Mr. Johnson’s care manager had stopped working with him after deciding he was not ready to make changes.

“Are we ready to try it again?” Dr. Busha asked him.

Mr. Johnson agreed to let the care manager contact him, and to return for a follow-up visit in two months.

Such efforts, said Mr. Murphy, the system’s chief executive, will remain “highly relevant” even if the Affordable Care Act is repealed.

The push toward a “risk-based” model over traditional fee-for-service medicine has spread beyond Medicare and Medicaid to private insurers. And the Obama administration has been testing new ways to save money on all sorts of medical care. Some of the experiments, overseen by an office created under the Affordable Care Act, have shown promise. But evaluating results is difficult.

“It may be good in theory,” Dr. John M. Thomas, a primary care physician at an IU Health practice in Lafayette, said of Dr. Busha’s system of quality measurements. “But there are a lot of flaws.”

For example, he explained, rather than risk being paid less because some patients have uncontrolled diabetes, doctors could tell those patients, “I’m sorry, you’re not in compliance with your medications, and I don’t want to be your physician.”

Dr. Busha said he was used to hearing such arguments.

“I have that conversation on a weekly basis,” he said. “You know: ‘What if my patients don’t believe in immunizations? Why am I held accountable for that?’”

He added, “We kind of tell them, ‘It’s your job to convince them.’”

Suddenly, Cost Counts

When IU Health discovered that a knee surgeon was using “bone cement” costing $300 a patient while another achieved the same results for $84, the first doctor was promptly informed. He switched.

IU Health now posts a color-coded “value tracker” in operating rooms that gives a green light to lower-cost surgical products, a red light to high-cost items and a yellow light to those in between.

“A huge cultural shift,” Dr. Anthony T. Sorkin, the medical director of orthopedics, said of the changes in his department — for the surgeons and the patients.

The IU Health system performed 3,900 hip- and knee-replacement operations in the year that ended on June 30. But it is not enough for doctors just to replace a knee or a hip. They are under pressure, from Medicare and private insurers, to manage and coordinate care for their patients before and after surgery. And, they say, payment for their services is continually being squeezed.

Doctors have three main ways to cut costs: improve the condition of patients before surgery, look for savings in every item used in the operating room (gloves, gowns, syringes, surgical tools, sutures, sponges and the implant itself), and send patients to nursing homes that strive to shorten the length of stay.

“I’ve been an orthopedic surgeon for 18 years,” Dr. Sorkin said. “For many of those years, I never once considered the cost for nursing homes.”

Why such attention to cost? In 67 geographic areas, including Indianapolis, Medicare now sets a target price for joint-replacement procedures. That target covers not only doctor services and hospital care but also 90 days of followup services like physical therapy, home health care and nursing-home stays. Hospitals are at risk: Medicare can pay bonuses or impose penalties, depending on whether spending targets and quality standards set by the government are met.

“We worry about 90 days of care, 90 days of Medicare spending, not just the brief time a patient spends in the hospital,” Dr. Sorkin said.

The joint-replacement program was one of the main targets of the letter that Mr. Price and other Republicans wrote to the Obama administration in September, complaining that such programs should be tested on a “voluntary, limited-scale basis” with no requirement for doctors to participate.

But in Indianapolis, the results have been promising. By working closely with nursing homes, IU Health halved the length of stay for patients recuperating from surgery, to an average of 12 days from 24 days in early 2016.

Doctors and nurses understand the need for change, but some still have concerns.

“These reforms are all intended to slow down the consumption of health care resources in the United States,” said Dr. Meneghini, who is the director of joint-replacement at Saxony Hospital here in Fishers. “We are careening at a rapid rate to a two-tier system. The public who can’t afford it goes to a public hospital and gets free health care. Those who have money get to pay for really nice care.”

A Mind Unchanged

The Health Care Revolution

Justin Kloski learned that he qualified for Medicaid under the worst of circumstances. The student and part-time lawncompany worker had lost 20 pounds, could not shake a nagging cough and was sleeping 14 hours a day when he decided to visit a clinic in Muncie, Ind., that provides free care for the poor and uninsured. A clinic employee invited Mr. Kloski, now 28, to apply for Medicaid.

A few days later, he took his new coverage to the emergency room at IU Health Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie. A CT scan found a 15-centimeter tumor in his chest, so big it was pressing on his windpipe. In May 2015, he learned he had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a form of cancer that is curable if caught early.

The Affordable Care Act, and Governor Pence’s decision to go against many other Republican governors and expand Medicaid under the law, may well have saved Mr. Kloski’s life.

He is among more than 400,000 Indiana residents — many of them previously uninsured — who have enrolled in Medicaid since Mr. Pence expanded it in 2015, the 10th Republican governor to do so. Under the terms of the health law, anyone with income up to 138 percent of the poverty level, or approximately $16,500 a year for an individual, now qualifies in states that opt to expand the program.

IU Health says it receives more Medicaid payments than any other health care provider in the state. Since the expansion began, the percentage of patients with Medicaid has grown to 23.2 from 207.

At the same time, the percentage of IU Health patients who are uninsured has fallen to 2.2 from 5.

In 2015 alone, the health system enrolled 14,000 people in Medicaid or private coverage, sometimes even signing up patients as they lay in hospital beds.

“We went all in because it’s a pretty big deal to us,” said Jonathan W. Vanator, IU Health’s vice president for revenue cycle services.

In the first nine months of last year, IU Health officials said, the amount of bad debt owed by patients and referred to collection agencies totaled $233 million, a 23 percent reduction from the comparable period in 2015, thanks largely to Mr. Obama’s health law.

But, the officials added, these gains have been largely offset by cuts in Medicare reimbursements and other federal funds under a law that has given and taken away.

Mr. Murphy is among many hospital executives now anxious about the possibility of seeing a bump in uninsured patients if the health law is repealed, while not getting back the federal funds they gave up under the health law. “I do think it would be problematic if part of the deal was changed and not the whole deal,” he said.

Mr. Pence expanded Medicaid only after the Obama administration agreed to let Indiana do it in its own way: Instead of getting virtually free coverage, as Medicaid recipients in many other states do, people enrolled in Indiana’s expansion pay up to 5 percent of their income toward it. Mr. Trump appears interested in promoting Indiana’s “personal responsibility” model: He has picked its chief architect, Seema Verma, to run the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Since Mr. Kloski had no income when he enrolled, he paid $1 a month; he has since been classified as “medically frail” and does not have to pay anything.

Medicaid has paid for virtually all of his cancer care, including a one-week hospitalization after the diagnosis, months of chemotherapy, and frequent scans and blood tests.

But Mr. Kloski and his mother, Renee Epperson, are still not fans of the health law over all. They believed that it required that Mr. Kloski be dropped, when he turned 26, from the health plan his mother has through her job at Target — not understanding that it was the law that kept him on the plan until he was 26.

Mr. Kloski paid a penalty for going uninsured in 2014 rather than even explore whether he might qualify for a subsidy and find an affordable private plan through the marketplaces.

“There were so many horror stories about how expensive it was going to be,” Ms. Epperson, 47, recalled. “Justin said, ‘I’m not even going to try it, Mom.’”

And until they were interviewed for this article, the mother and son did not know that the law was responsible for the expansion of Medicaid that Mr. Kloski benefited from. Neither voted in last year’s presidential election; Ms. Epperson said that she disliked both candidates, and that even though Hillary Clinton supported the Affordable Care Act, she found Mrs. Clinton’s positions unacceptable on too many other issues, like abortion rights, to support her.

Still, she said, she ardently hopes that Mr. Trump and the Republican Congress will continue allowing low-income adults like her son to qualify for Medicaid.

“Oh my God, yes,” she said. “Absolutely.”

As for Mr. Murphy, IU Health’s chief executive, he said that while he did not want to think too much about changes that were still hypothetical, the prospect of losing the Medicaid expansion made him anxious.

“I worry about lots of things,” he said. “That list is probably 50 long, and this is definitely on that list.”

No comments:

Post a Comment